Most people are familiar with the lobsters that grace many New England tables this time of year. The American/Atlantic/Maine lobster,

Homarus americanus, is a well-known icon of the northeast part of the country and countless

J. Crew summer prints.

Therefore, we're not going to discuss them further here today. Perhaps once I read

The Secret Life of Lobsters I'll have something interesting to say about them beyond that they're apparently good with drawn butter.

This post is about the bizarro-lobsters of the deep seas. Sharon introduced me to a new one today, so let's view that one first!

The

slipper lobster is not a "true lobster" -- it is instead more closely related to some of the other bizarro lobsters, the spiny and furry lobsters. They are

achelate, meaning they have no claws. This makes them easy prey for humans, and indeed, if you Google "slipper lobster" you will find their tail meat for sale. (Of course, there is no claw meat to speak of.) Some of them are actually referred to as

bugs, which is rather entertaining. No word yet on their position as a sustainable seafood. Not much seems to be known about them, if Wikipedia is at all accurate. Maybe it's better that way.

Next up:

spiny lobsters. Popular for eating, also known as "rock lobster", and very colorful. Also, the only arthropod (as far as I know) that was immortalized in song by

Fred Schneider (who is also very colorful). Interestingly, spiny lobsters have a unique form of sound production involving rubbing their antennae against a file-like protrusion. I'm not really sure what's going on there, but they're the only ones that do it, so that's neat.

I would tell you something about the

furry lobsters, but there doesn't seem to be much to tell. (Except that if you start thinking too hard about the concept of a furry lobster, it can sort of hurt your brain.) Besides, you don't want to hear about

true furry lobsters, you want to hear about

this:

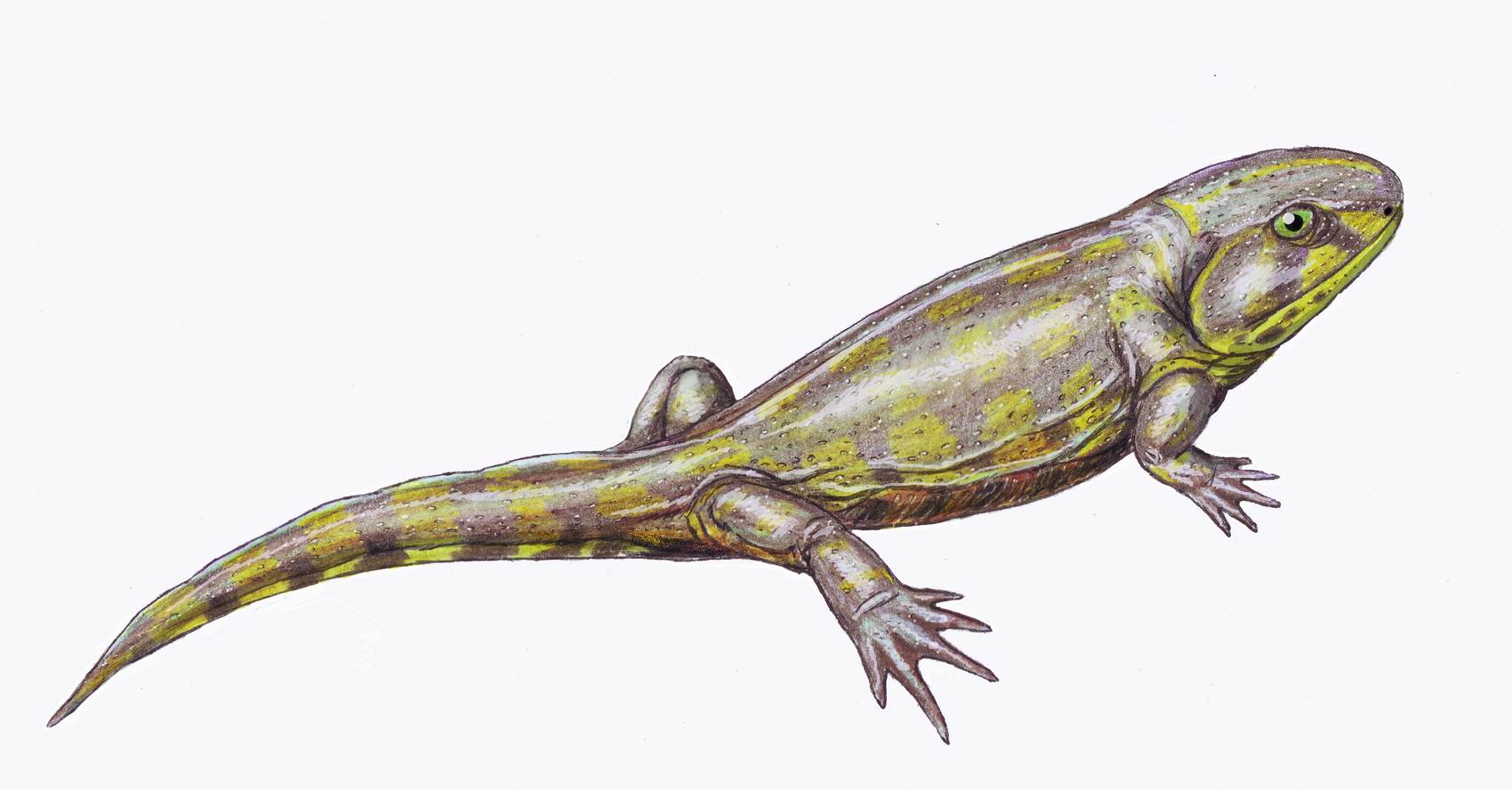

Kiwa hirsuta

Kiwa hirsuta, also entertainingly known as the yeti lobster, is not a true lobster or in the Achelate group with the other "bizarro" lobsters.

Kiwa is in its own brand-new family, Kiwaidae, all by its lonesome. See, this beautiful,

samba-dancing lobster, which you might be tempted to call a furry lobster but

is not, was only discovered in 2005, chillin' at the bottom of the Pacific ocean. It lives on hydrothermal vents (so, maybe not chillin', per se), is pretty much blind, and may use all those "hairs" to detox after hanging around the vents, which spew mineral toxins.

My favorite part of this lobster is not that it's yellow, not that it's furry, and not that it's a deep-sea critter. (Although I love deep-sea critters, they're so bizarre!) My favorite part is that it was only found three years ago. I spent most of my life on a planet where no humans knew this thing existed! I suppose

Kiwa knew it existed, if decapods can have self-awareness. But

we did not know. There are still new things out there to find, if we look hard enough! (As I mentioned in my previous post, the world is just awesome.)

So there you have it. OK, true, none of these critters are true lobsters, but they all have lobster in their names and are therefore acceptable for a not-entirely-scientific blog post. (I didn't name the blog "Correctly Taxonomied Creatures," did I?) I hope you enjoyed your bizarro lobsters. Now please pass me some drawn butter, I want to dip my asparagus in it.

This is my best Habropoda laboriosa photo to date, you can actually see her face in this one, yay! Also take a look at all the pollen on her legs! I wish her hundreds of fat children.

This is my best Habropoda laboriosa photo to date, you can actually see her face in this one, yay! Also take a look at all the pollen on her legs! I wish her hundreds of fat children.