Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

Where I've Been

Before I start writing up what I'm doing right now, here's a little recap of the last 18 months or so, to put my absence in perspective. Not the most exciting post, but it will put my forthcoming field season posts in perspective!

From October 2009 through March 2010, I wrote my preliminary proposal for my thesis project. Most people take their qualifying exam (aka "Quals") first, but I did things backwards. I'm wacky like that.

As part of my preliminary proposal, I spend a lot of time using GIS to select sites for my study. Since I'm comparing effects of landscape at different scales, site selection is a huge aspect of my project. In the end, I came up with 16 sites and two control sites, all blueberry fields in southern New Jersey. This took most of March.

On April 1st, I started training a field crew of five people, including myself. It was a good thing we started early, because last year was one of the earliest blooms on record for blueberry in this region. Our first day of data collection was April 15, which was already a few days into bloom; we were done with data collection on May 5. Short field season!

From May 6 or so right up to last month, I have been analyzing my data. Really. It's still ongoing, but I had to take a break from analyzing the data to collect more data, starting... probably next week. More on that to follow.

But, data analysis isn't all I do! (Although, it's most of what I do.) I also spent a few months studying for my quals (and passed, thank Darwin that's over!), gave a 10-minute talk at the Entomological Society of America meeting in San Diego last December, started writing a paper with my advisor, and have learned a bit of programming in R. I also got a great teaching gig that lets me teach only in the Fall semester, so I can focus on my field season in the spring. I've also learned to bake foccacia. Overall, it's been a busy 18 months!

I'll write more about the current field season soon, but in the meantime, here are some early-season critter photos. Enjoy!

From October 2009 through March 2010, I wrote my preliminary proposal for my thesis project. Most people take their qualifying exam (aka "Quals") first, but I did things backwards. I'm wacky like that.

As part of my preliminary proposal, I spend a lot of time using GIS to select sites for my study. Since I'm comparing effects of landscape at different scales, site selection is a huge aspect of my project. In the end, I came up with 16 sites and two control sites, all blueberry fields in southern New Jersey. This took most of March.

On April 1st, I started training a field crew of five people, including myself. It was a good thing we started early, because last year was one of the earliest blooms on record for blueberry in this region. Our first day of data collection was April 15, which was already a few days into bloom; we were done with data collection on May 5. Short field season!

From May 6 or so right up to last month, I have been analyzing my data. Really. It's still ongoing, but I had to take a break from analyzing the data to collect more data, starting... probably next week. More on that to follow.

But, data analysis isn't all I do! (Although, it's most of what I do.) I also spent a few months studying for my quals (and passed, thank Darwin that's over!), gave a 10-minute talk at the Entomological Society of America meeting in San Diego last December, started writing a paper with my advisor, and have learned a bit of programming in R. I also got a great teaching gig that lets me teach only in the Fall semester, so I can focus on my field season in the spring. I've also learned to bake foccacia. Overall, it's been a busy 18 months!

I'll write more about the current field season soon, but in the meantime, here are some early-season critter photos. Enjoy!

Monday, October 26, 2009

The Naming of Things

A few things on naming caught my attention recently.

First there was this article (from the NYTimes, of course) which is on taxonomy in general and on native taxonomies in particular. How good are you at distinguishing between bird names and fish names in on naming birds and fish in the Huambisa language?

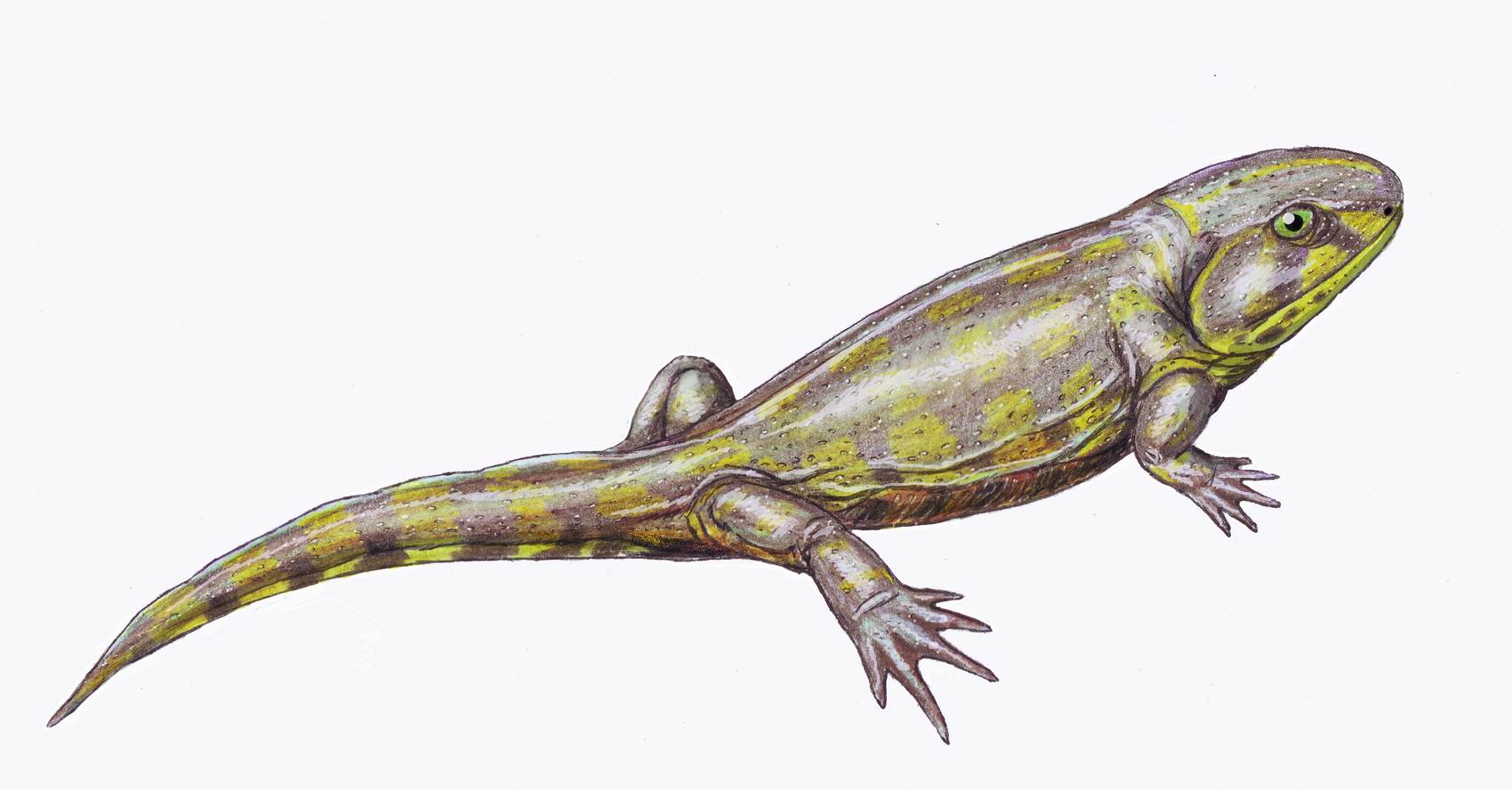

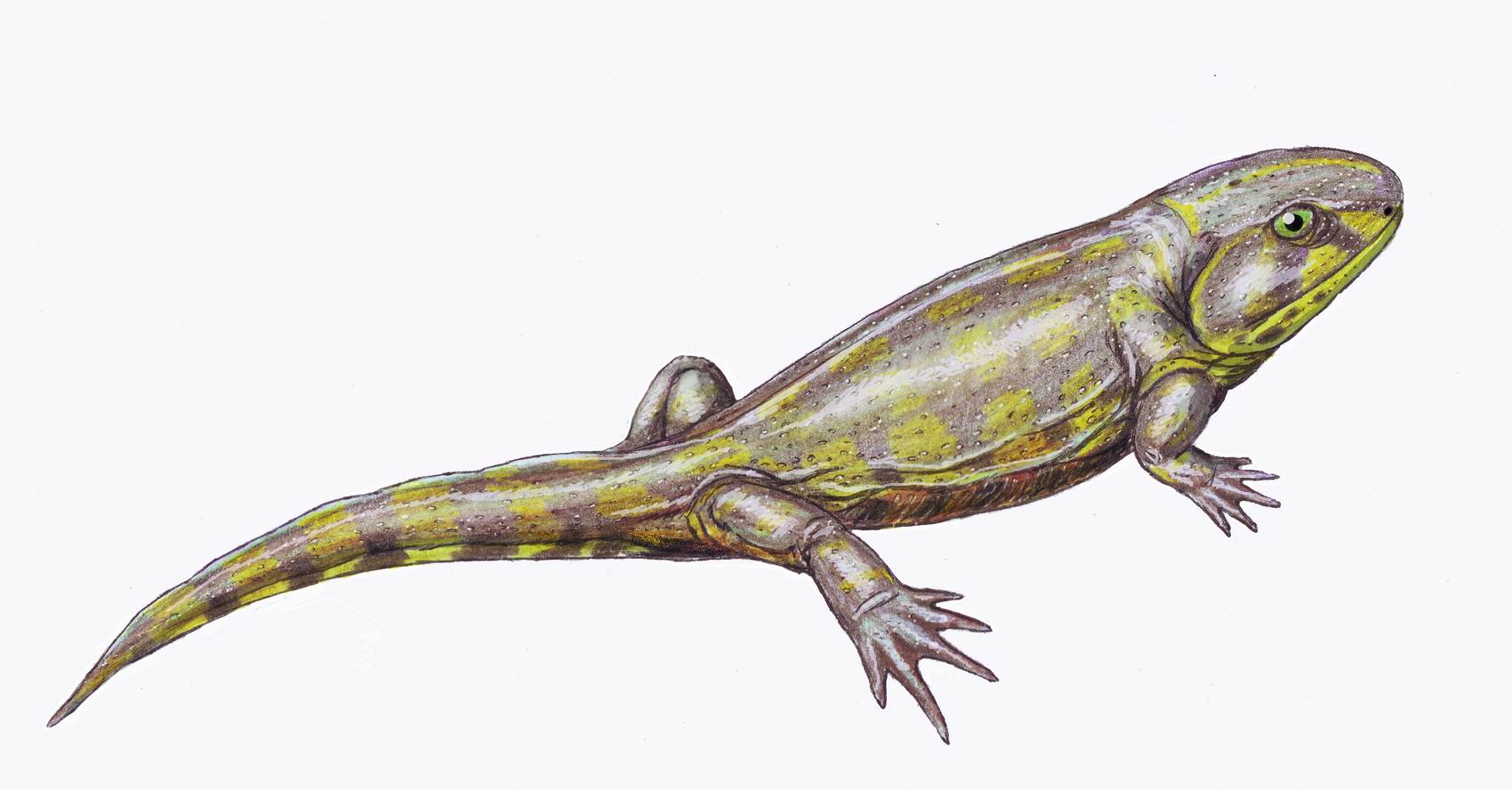

Then I came across this linked from a faculty member's website: Curiosities of Biological Nomenclature. There's a lot to discover here. From the "Interesting Translations" section, I can't help giggling at Eucritta melanolimnetes (a fossil amphibian), which translates to "creature from the black lagoon", and at Vampyroteuthis infernalis, a squid relative, aka "the vampire squid from hell."

My favorite section, of course, is the puns. Here's one of the best bits on the whole site:

Finally, I was reading about native plants the other day... if I told you you had Ambrosia and Lotus growing all over your yard, you'd probably think that was great, right?

Not if you have allergies. Ambrosia is the genus name for ragweed (the name has to do with the immortality of the species). Lotus is a little better -- it's a genus of plants known as deervetches, but certainly desn't look anything like what most people think of as a lotus.

First there was this article (from the NYTimes, of course) which is on taxonomy in general and on native taxonomies in particular. How good are you at distinguishing between bird names and fish names in on naming birds and fish in the Huambisa language?

Then I came across this linked from a faculty member's website: Curiosities of Biological Nomenclature. There's a lot to discover here. From the "Interesting Translations" section, I can't help giggling at Eucritta melanolimnetes (a fossil amphibian), which translates to "creature from the black lagoon", and at Vampyroteuthis infernalis, a squid relative, aka "the vampire squid from hell."

The Creature from the Black Lagoon... is actually sort of cute.

My favorite section, of course, is the puns. Here's one of the best bits on the whole site:

Balaenoptera musculus Linneaus (blue whale) Musculus could mean "muscular," but it can also be interpreted as "little mouse." Linne would have known this and, given his sense of humor, may have intended the ironic double meaning.That Linne... what a wacky guy!

Finally, I was reading about native plants the other day... if I told you you had Ambrosia and Lotus growing all over your yard, you'd probably think that was great, right?

Not if you have allergies. Ambrosia is the genus name for ragweed (the name has to do with the immortality of the species). Lotus is a little better -- it's a genus of plants known as deervetches, but certainly desn't look anything like what most people think of as a lotus.

Wednesday, June 10, 2009

Once Upon a Field Season

HELLO WORLD!

I'm BACK.

This is a blueberry field on April 22. Notice that it is 1) not in bloom and 2) raining.

A different field, on May 4. You may notice that it is still quite grey and, in fact, the day this picture was taken it was also raining. (This will be the ongoing theme of field season.)

The ongoing dismal weather grounded the local turkey vulture population. They liked to hang out in one particular dead tree near this field. You can see them in the above photo, but here is a close-up.

The next day was another rainy one. Since bees don't like the rain very much, I didn't see very many. I did see some other beautiful little things:

I'm BACK.

This is a blueberry field on April 22. Notice that it is 1) not in bloom and 2) raining.

A different field, on May 4. You may notice that it is still quite grey and, in fact, the day this picture was taken it was also raining. (This will be the ongoing theme of field season.)

The ongoing dismal weather grounded the local turkey vulture population. They liked to hang out in one particular dead tree near this field. You can see them in the above photo, but here is a close-up.

The next day was another rainy one. Since bees don't like the rain very much, I didn't see very many. I did see some other beautiful little things:

I think this tiny arachnids is some sort of crab spider. That flower is about 8 mm long.

Back at the field station, I saw this little guy puffing himself up against the cold weather. A few buzzed me at my field sites as well, but I didn't get any photos. Too bad the light was so dull, you can't really see the ruby-red.

Back at the field station, I saw this little guy puffing himself up against the cold weather. A few buzzed me at my field sites as well, but I didn't get any photos. Too bad the light was so dull, you can't really see the ruby-red.

I placed a call to the police to find out whether I needed to evacuate my field site. Fortunately it was a controlled burn and was put out quickly. It smelled very nice, actually, since they were burning a patch of pine forest.

I placed a call to the police to find out whether I needed to evacuate my field site. Fortunately it was a controlled burn and was put out quickly. It smelled very nice, actually, since they were burning a patch of pine forest.

Oh! Right! I also saw some bees!

Since it was a very early season, most of the Bombus I saw were queens. You can tell Bombus queens from workers by the fact that the queens are as big as your thumb and sound like helicopters, while the workers are relatively quite small (especially early in the season). This is probably Bombus impatiens. Fun fact: bumblebees are actually as soft as they look.

Since it was a very early season, most of the Bombus I saw were queens. You can tell Bombus queens from workers by the fact that the queens are as big as your thumb and sound like helicopters, while the workers are relatively quite small (especially early in the season). This is probably Bombus impatiens. Fun fact: bumblebees are actually as soft as they look.

A number of other native bees appeared at my field sites, although generally not in any great numbers. This is one of my favorite native bees. It's in the genus Colletes and the orange hairs make them look like they're wearing tiny fox-fur jackets. Eventually they get around to sticking their heads into a few flowers, but they don't work constantly like the bumblebees do.

A number of other native bees appeared at my field sites, although generally not in any great numbers. This is one of my favorite native bees. It's in the genus Colletes and the orange hairs make them look like they're wearing tiny fox-fur jackets. Eventually they get around to sticking their heads into a few flowers, but they don't work constantly like the bumblebees do.

I'll post again soon, but it's been so long that I have to split things up over several entries. In the meantime, click on the photos to see them larger -- they look really good full-screen, thank goodness I learned how to use the macro on the camera before the season started. Enjoy!

Back at the field station, I saw this little guy puffing himself up against the cold weather. A few buzzed me at my field sites as well, but I didn't get any photos. Too bad the light was so dull, you can't really see the ruby-red.

Back at the field station, I saw this little guy puffing himself up against the cold weather. A few buzzed me at my field sites as well, but I didn't get any photos. Too bad the light was so dull, you can't really see the ruby-red.Eventually the weather dried out a bit and we had clear skies for a few days. Of course, the Pinelands are a fire-happy ecosystem, so when I looked up and saw this:

I placed a call to the police to find out whether I needed to evacuate my field site. Fortunately it was a controlled burn and was put out quickly. It smelled very nice, actually, since they were burning a patch of pine forest.

I placed a call to the police to find out whether I needed to evacuate my field site. Fortunately it was a controlled burn and was put out quickly. It smelled very nice, actually, since they were burning a patch of pine forest.Oh! Right! I also saw some bees!

Since it was a very early season, most of the Bombus I saw were queens. You can tell Bombus queens from workers by the fact that the queens are as big as your thumb and sound like helicopters, while the workers are relatively quite small (especially early in the season). This is probably Bombus impatiens. Fun fact: bumblebees are actually as soft as they look.

Since it was a very early season, most of the Bombus I saw were queens. You can tell Bombus queens from workers by the fact that the queens are as big as your thumb and sound like helicopters, while the workers are relatively quite small (especially early in the season). This is probably Bombus impatiens. Fun fact: bumblebees are actually as soft as they look. A number of other native bees appeared at my field sites, although generally not in any great numbers. This is one of my favorite native bees. It's in the genus Colletes and the orange hairs make them look like they're wearing tiny fox-fur jackets. Eventually they get around to sticking their heads into a few flowers, but they don't work constantly like the bumblebees do.

A number of other native bees appeared at my field sites, although generally not in any great numbers. This is one of my favorite native bees. It's in the genus Colletes and the orange hairs make them look like they're wearing tiny fox-fur jackets. Eventually they get around to sticking their heads into a few flowers, but they don't work constantly like the bumblebees do.I'll post again soon, but it's been so long that I have to split things up over several entries. In the meantime, click on the photos to see them larger -- they look really good full-screen, thank goodness I learned how to use the macro on the camera before the season started. Enjoy!

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Two Centuries Ago...

Once in a while, maybe not quite once a century, a person will come along who will have the Next Big Idea, who will shape the course of history. A person that can change the way people think, and can in fact still affect our ideas today.

Oddly enough, on this day in 1809, two people were born on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean who would come to shape their century. One, of course, was our sixteenth president, Abraham Lincoln.

Oddly enough, on this day in 1809, two people were born on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean who would come to shape their century. One, of course, was our sixteenth president, Abraham Lincoln.

The other was Charles Darwin.

Happy birthday, Charles Darwin!

This year is not only the bicentennial of Darwin's birth. He published The Origin of Species at the age of fifty, which makes this year the 150th anniversary of its publication, as well. So as you might imagine, this is a jubilee year for evolutionary biologists. There are conferences going on all month, commemorative articles, magazines and journals, and other fun and celebration. Check out the Darwin Day official website to learn more about what's going on this month and all year!

Celebrating Darwin Day is nothing new; scientists were celebrating him by 1909. This year, of course, is a Big Round Number year, so there are more things going on than usual. Have a very happy Darwin Day!

For your reading pleasure:

Celebrating Darwin Day is nothing new; scientists were celebrating him by 1909. This year, of course, is a Big Round Number year, so there are more things going on than usual. Have a very happy Darwin Day!

For your reading pleasure:

- The Origin of Species, available through Google Books.

- The Descent of Man, same

- Newsweek article about Darwin and Lincoln

- Smithsonian Magazine article about Darwin and Lincoln, and the table of contents for the February 2009 with them on the cover!

Labels:

citizen science,

education,

evolution,

fun stuff,

science

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

DIY Dairy II: The Curdling

A while back, I talked about my interest in making my own yogurt.

Tonight, I'm going to try a new experiment: I'm going to make my own cheese.

As before, you may have your doubts, reminding me that caves are often an integral part of the cheese industry and that I live in an apartment (and not a very cave-like one, at that).

But Mr. Bittman says it can be done at home, and quite easily. And, I have an important ingredient: motivation. When I lived in Manhattan, I had the world's best sheep milk ricotta available whenever I wanted it from the Fairway cheese counter. I remember the first time I tried it; I had asked the cheesemonger on duty where I might find the ricotta, and he said to me, "Well, that Polly-O stuff and all the others are around that corner, but... try this." He produced a spoonful of the creamiest, lightest, most delicious ricotta I had ever tasted. (They kept it behind the cheese counter, available only by request.) I made a fine baked pasta that night, and every bite was a song of praise to the sheep that had produced the milk. That ricotta tasted of excellent milk, open green pastures and fresh air. Polly-O and all the others, after that, only tasted like processed, fake food.

Sadly, I do not currently have a source for this miraculous ricotta. When the farmer's market season fires up again I will be able to get some, but I have a tomato-blue cheese tart planned for Thursday and I need some good ricotta today.

Which is why I am going to make my own cheese.

The basic principle of cheese-making is this: if you start with milk and add something that acidifies it, the proteins will stick together in clumps (curds) and separate from the liquid (whey). Strain the whey from the curds, press them together, add salt and other flavors. Age as you see fit. A simple process in principle, but with lots of room for improvisation.

When you acidify the milk with an acid, you get something like feta or cottage cheese. However, most cheeses are made at least in part with the help of our friends, the bacteria. Bacteria break down the sugar in milk (lactose) and turn it into organic acid (lactic acid). This acid then causes the reaction I described above. You already know this if you have encountered milk that is very far beyond its expiration date; it smells sour and gets a bit clumpy at the bottom.

The recipe Mr. Bittman gives calls for buttermilk, which is made by innoculating milk with a bacterial culture, similar to a very thin yogurt. (Historically, buttermilk is what remained after skimming the milk to make butter, but that is rarely available in your average supermarket today.) The milk is simmered for a few minutes, the buttermilk is added all at once, and, with a little luck, everything will curdle nicely. The whole mixture is put through a cheesecloth, salted, and drained.

I will let you know how it goes tonight in mylaboratory kitchen. I'm using cow milk, since sheep milk is not available at Stop n Shop. In the meantime, check out the Wikipedia page on cheese. Interesting things to know:

PS: A little late, but... Happy New Year!

Tonight, I'm going to try a new experiment: I'm going to make my own cheese.

As before, you may have your doubts, reminding me that caves are often an integral part of the cheese industry and that I live in an apartment (and not a very cave-like one, at that).

But Mr. Bittman says it can be done at home, and quite easily. And, I have an important ingredient: motivation. When I lived in Manhattan, I had the world's best sheep milk ricotta available whenever I wanted it from the Fairway cheese counter. I remember the first time I tried it; I had asked the cheesemonger on duty where I might find the ricotta, and he said to me, "Well, that Polly-O stuff and all the others are around that corner, but... try this." He produced a spoonful of the creamiest, lightest, most delicious ricotta I had ever tasted. (They kept it behind the cheese counter, available only by request.) I made a fine baked pasta that night, and every bite was a song of praise to the sheep that had produced the milk. That ricotta tasted of excellent milk, open green pastures and fresh air. Polly-O and all the others, after that, only tasted like processed, fake food.

Sadly, I do not currently have a source for this miraculous ricotta. When the farmer's market season fires up again I will be able to get some, but I have a tomato-blue cheese tart planned for Thursday and I need some good ricotta today.

Which is why I am going to make my own cheese.

The basic principle of cheese-making is this: if you start with milk and add something that acidifies it, the proteins will stick together in clumps (curds) and separate from the liquid (whey). Strain the whey from the curds, press them together, add salt and other flavors. Age as you see fit. A simple process in principle, but with lots of room for improvisation.

When you acidify the milk with an acid, you get something like feta or cottage cheese. However, most cheeses are made at least in part with the help of our friends, the bacteria. Bacteria break down the sugar in milk (lactose) and turn it into organic acid (lactic acid). This acid then causes the reaction I described above. You already know this if you have encountered milk that is very far beyond its expiration date; it smells sour and gets a bit clumpy at the bottom.

The recipe Mr. Bittman gives calls for buttermilk, which is made by innoculating milk with a bacterial culture, similar to a very thin yogurt. (Historically, buttermilk is what remained after skimming the milk to make butter, but that is rarely available in your average supermarket today.) The milk is simmered for a few minutes, the buttermilk is added all at once, and, with a little luck, everything will curdle nicely. The whole mixture is put through a cheesecloth, salted, and drained.

I will let you know how it goes tonight in my

- The history of cheese predates recorded history.

- Acid-set cheeses (as opposed to rennet-set) will not melt; they have a different kind of protein matrix holding them together and only get firmer as they cook. (Paneer is a good example.)

- The US is the world's biggest producer of cheese, but France is the biggest exporter. But the true title of cheese-eating champions goes to Greece, which eats more cheese per capita than any other country. (However, three quarters of it is feta cheese.) France is a close second.

PS: A little late, but... Happy New Year!

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

Small and Blue and Beautiful

Yesterday I blogged about something very small.

Today I'd like to call your attention to some articles that talk about something very big.

Forty years ago today, astronauts took this historic photo, "Earthrise". I didn't remember that until reading the editorials in the Times, of course, since I wasn't around yet. Some say that this image helped jump-start the environmental movement.

Anyway, the articles from today and from 1968 are worth checking out. Here is today's editorial reflecting on 1968 and now; this op-ed piece observes that while *we* may be fragile, life on earth has endured worse than humans and survived. From the first editorial, click on the "Related Articles" links to download some of the original articles from 1968, which are not available as web pages. This photograph is also so famous that it has its own Wikipedia page.

From the 1968 editorial:

PS: For more on "Earthrise" and a short video clip from the Apollo 8 mission, visit this Dot Earth post from today.

Today I'd like to call your attention to some articles that talk about something very big.

Forty years ago today, astronauts took this historic photo, "Earthrise". I didn't remember that until reading the editorials in the Times, of course, since I wasn't around yet. Some say that this image helped jump-start the environmental movement.

Anyway, the articles from today and from 1968 are worth checking out. Here is today's editorial reflecting on 1968 and now; this op-ed piece observes that while *we* may be fragile, life on earth has endured worse than humans and survived. From the first editorial, click on the "Related Articles" links to download some of the original articles from 1968, which are not available as web pages. This photograph is also so famous that it has its own Wikipedia page.

From the 1968 editorial:

To see the earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold — brothers who know now they are truly brothers.Lovely.

PS: For more on "Earthrise" and a short video clip from the Apollo 8 mission, visit this Dot Earth post from today.

Labels:

conservation,

greener life,

habitat,

new york times,

science,

travel

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

The 40 Million Year Old Virgins

Imagine, on this cold near-solstice day, that in the spring you go out to a nearby pond and collect a sample of water. You bring it home, put a drop on a microscope slide, and take a look at the pond's microcosm. Zooming around your sample are a wide variety of "wee beasties" -- you might see a blobby amoeba, a diflagellate like Chlamydomonas, and many other single-cell organisms.

Then a large, mostly transparent creature comes into focus. It doesn't look like all the others. It's far more complex, like a mechanical sea creature in miniature. Something like this:

Beautiful, isn't it?

This is a rotifer, a tiny aquatic animal in the phylum Rotifera. It may be small, but it is bilaterally symmetric and has a distinct head. It pulls in food particles with the wheel-like structure (hence "rotifer" or "wheel-bearer") around its mouth.

The rotifer pictured above is, however, special for another reason. This is a bdelloid rotifer (the b is silent). You are looking at a species that has not mated in at least 40 million years.

All bdelloid rotifers are female, and they reproduce by parthenogenesis. (Olivia Judson talks about them at length in her excellent book, Dr. Tatiana's Sex Advice to All Creation, and wrote a column about them in June.) This is highly unusual, since it is generally thought that gene exchange is an important mechanism for evolution. Yet with no sexual reproduction, how could the bdelloids have speciated so intensely (there are estimated to be 350 species) and persisted for so long?

Researchers at Harvard and Woods Hole may have the answer. In a paper published in Nature in May, geneticists found that when they analyzed rotifer DNA, they found genes known to occur in plants, fungi, and bacteria. This evidence suggests that rotifers have been engaging in horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

HGT is a well-known phenomenon, but it was primarily known from single-celled organisms. For example, many bacteria are known to incorporate novel genes from other members of the population, or even from other species. When you only have one cell, it's not too hard to get a novel gene into that cell. Most animals, which are by definition multicellular, can't do this; most of us pass our genes to our offspring via specialized reproductive cells, which are typically hidden away inside gonads. Unless novel genes make it to the sex cells and can therefore be passed on to the next generation, HGT has not taken place. (Passing genes to your offspring is vertical inheritance.)

Bdelloids, however, appear to be capable of massive horizontal gene transfer. Gladyshev et al. point out that this is not a case of rotifers simply retaining genes that are common to all life; that case is both extremely unlikely and not supported by the data. Instead, they suggest,

With their proclivity for moist habitats, bdelloids also run the risk of dessication. They are able to withstand repeated dessication; in fact, it might be necessary for the continued success of the entire class, since this appears to be the mechanism by which they gain new genetic material. The authors conclude,

So, in conclusion, bdelloids have done away with sex as we know it, but periodically get turned into rotifer jerky, incorporate new genes while their cells are cracked open, and when reconstituted and repaired produce more copies of themselves, thus passing new genes to the next generation.

Lots of questions remain; for example, what are rotifers doing with all these new genes? (One example is a bacterial gene for cell walls; no one knows how an animal might make use of a cell wall.) I will keep you posted on all rotifer-related news updates. Stay tuned!

References

Gladyshev, E. et al. "Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bdelloid Rotifers." Science 30 May 2008: Vol. 320. no. 5880, pp. 1210 - 1213

Judson, O. "The Weird Sisters" The New York Times, June 3, 2008.

Then a large, mostly transparent creature comes into focus. It doesn't look like all the others. It's far more complex, like a mechanical sea creature in miniature. Something like this:

Beautiful, isn't it?

This is a rotifer, a tiny aquatic animal in the phylum Rotifera. It may be small, but it is bilaterally symmetric and has a distinct head. It pulls in food particles with the wheel-like structure (hence "rotifer" or "wheel-bearer") around its mouth.

The rotifer pictured above is, however, special for another reason. This is a bdelloid rotifer (the b is silent). You are looking at a species that has not mated in at least 40 million years.

All bdelloid rotifers are female, and they reproduce by parthenogenesis. (Olivia Judson talks about them at length in her excellent book, Dr. Tatiana's Sex Advice to All Creation, and wrote a column about them in June.) This is highly unusual, since it is generally thought that gene exchange is an important mechanism for evolution. Yet with no sexual reproduction, how could the bdelloids have speciated so intensely (there are estimated to be 350 species) and persisted for so long?

Researchers at Harvard and Woods Hole may have the answer. In a paper published in Nature in May, geneticists found that when they analyzed rotifer DNA, they found genes known to occur in plants, fungi, and bacteria. This evidence suggests that rotifers have been engaging in horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

HGT is a well-known phenomenon, but it was primarily known from single-celled organisms. For example, many bacteria are known to incorporate novel genes from other members of the population, or even from other species. When you only have one cell, it's not too hard to get a novel gene into that cell. Most animals, which are by definition multicellular, can't do this; most of us pass our genes to our offspring via specialized reproductive cells, which are typically hidden away inside gonads. Unless novel genes make it to the sex cells and can therefore be passed on to the next generation, HGT has not taken place. (Passing genes to your offspring is vertical inheritance.)

Bdelloids, however, appear to be capable of massive horizontal gene transfer. Gladyshev et al. point out that this is not a case of rotifers simply retaining genes that are common to all life; that case is both extremely unlikely and not supported by the data. Instead, they suggest,

It may be that HGT is facilitated by membrane disruption and DNA fragmentation and repair associated with the repeated desiccation and recovery experienced in typical bdelloid habitats, allowing DNA in ingested or other environmental material to enter bdelloid genomes.

With their proclivity for moist habitats, bdelloids also run the risk of dessication. They are able to withstand repeated dessication; in fact, it might be necessary for the continued success of the entire class, since this appears to be the mechanism by which they gain new genetic material. The authors conclude,

Although the adaptive importance of such massive HGT remains to be elucidated, it is evident that such events have frequently occurred in the genomes of bdelloid rotifers, probably mediated by their unusual lifestyle.

So, in conclusion, bdelloids have done away with sex as we know it, but periodically get turned into rotifer jerky, incorporate new genes while their cells are cracked open, and when reconstituted and repaired produce more copies of themselves, thus passing new genes to the next generation.

Lots of questions remain; for example, what are rotifers doing with all these new genes? (One example is a bacterial gene for cell walls; no one knows how an animal might make use of a cell wall.) I will keep you posted on all rotifer-related news updates. Stay tuned!

References

Gladyshev, E. et al. "Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer in Bdelloid Rotifers." Science 30 May 2008: Vol. 320. no. 5880, pp. 1210 - 1213

Judson, O. "The Weird Sisters" The New York Times, June 3, 2008.

Monday, December 15, 2008

Plants Fighting Back

On Tuesday I reached into the container of cilantro from the grocery store and quickly pulled my hand back in surprise. Something had hurt me! But what?

My thoughts went to some alarming places. Bits of metal? Shards of glass? I felt like I had been pricked by something sharp, but there were no marks on my fingertips. No blood was drawn.

I dumped all of the cilantro into a colander and moved it around with a fork. There in the middle was the culprit. Initially its camouflage had concealed it from sight, but on closer inspection it stood out from its surroundings.

Clearly, those are not cilantro leaves. Any guesses?

It turned out my instinct was correct, because the first page I pulled up on Wikipedia was stinging nettle, where I saw the above picture. The plant mixed with my cilantro was the spitting image.

What makes a stinging nettle sting? The sting is caused by a combination of chemicals, not just by the hairs alone which, although sharp, are tiny. Tiny and hollow, and filled with a combination of chemicals that give a noticeable irritation: acetylcholine, serotonin, and perhaps most importantly, histamine and possibly formic acid. Yikes.

Surprisingly, nettles are easily tamed, and can be made into tea or even eaten when young ( and cooked). They're also good for your hair, feature prominently in hippie-dippie shampoos, and are mixed into cattle feed to give the bovines shiny coats. My nettle, however, was transferred by fork to the trash bin, as I was in no mood to attempt to tame it. (And my hair is already quite shiny, thank you.) I do admire it for fighting back, though. As a vegetarian, I'm not really used to food that puts up much of a struggle, so this was an interesting interaction between me and a plant.

But I think I'll stick with cilantro just the same.

My thoughts went to some alarming places. Bits of metal? Shards of glass? I felt like I had been pricked by something sharp, but there were no marks on my fingertips. No blood was drawn.

I dumped all of the cilantro into a colander and moved it around with a fork. There in the middle was the culprit. Initially its camouflage had concealed it from sight, but on closer inspection it stood out from its surroundings.

Clearly, those are not cilantro leaves. Any guesses?

It turned out my instinct was correct, because the first page I pulled up on Wikipedia was stinging nettle, where I saw the above picture. The plant mixed with my cilantro was the spitting image.

What makes a stinging nettle sting? The sting is caused by a combination of chemicals, not just by the hairs alone which, although sharp, are tiny. Tiny and hollow, and filled with a combination of chemicals that give a noticeable irritation: acetylcholine, serotonin, and perhaps most importantly, histamine and possibly formic acid. Yikes.

Surprisingly, nettles are easily tamed, and can be made into tea or even eaten when young ( and cooked). They're also good for your hair, feature prominently in hippie-dippie shampoos, and are mixed into cattle feed to give the bovines shiny coats. My nettle, however, was transferred by fork to the trash bin, as I was in no mood to attempt to tame it. (And my hair is already quite shiny, thank you.) I do admire it for fighting back, though. As a vegetarian, I'm not really used to food that puts up much of a struggle, so this was an interesting interaction between me and a plant.

But I think I'll stick with cilantro just the same.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Sarah Palin Loses the Geneticist Vote

This is already burning up in the science-oriented part of the blogosphere, but I want to mention it here too.

I've talked before about how Sarah Palin is a heartless lawbreaker who would love to shoot every wolf in Alaska. But did you know she's also opposed to basic scientific research?

Well, more specifically, she doesn't know what she's talking about when it comes to research. Otherwise, why would she highlight spending on fruit fly research in Paris as a "pet project earmark"? Did no one in the McCain campaign bother to find out what kind of research they were doing? I hate to tell you this, Ms. Palin... but fruit flies are the favored lab animal for genetics research around the world, both in Paris and here in the good ol' USA. (Except for New Jersey, which is not part of the "real" America.)

I think PZ Meyers, who writes the excellent blog Pharyngula, said it best:

Oh, and he also threw in this disturbing but excellent point:

If you're interested in watching, Think Progress has a video clip of Palin delivering the remarks. You can read the original prepared text at the McCain campaign page, but they differ somewhat from what she actually said. (For example, sarcasm is not noted anywhere in the prepared text.)

With the election so near (I've been unable to think of anything else lately), I think it's important to recognize what a McCain victory would do to the scientific community. Government funding for basic research is non-negotiable.

I've talked before about how Sarah Palin is a heartless lawbreaker who would love to shoot every wolf in Alaska. But did you know she's also opposed to basic scientific research?

Well, more specifically, she doesn't know what she's talking about when it comes to research. Otherwise, why would she highlight spending on fruit fly research in Paris as a "pet project earmark"? Did no one in the McCain campaign bother to find out what kind of research they were doing? I hate to tell you this, Ms. Palin... but fruit flies are the favored lab animal for genetics research around the world, both in Paris and here in the good ol' USA. (Except for New Jersey, which is not part of the "real" America.)

I think PZ Meyers, who writes the excellent blog Pharyngula, said it best:

Yes, scientists work on fruit flies. Some of the most powerful tools in genetics and molecular biology are available in fruit flies, and these are animals that are particularly amenable to experimentation. Molecular genetics has revealed that humans share key molecules, the basic developmental toolkit, with all other animals, thanks to our shared evolutionary heritage (something else the wackaloon from Wasilla denies), and that we can use these other organisms to probe the fundamental mechanisms that underlie core processes in the formation of the nervous system — precisely the phenomena Palin claims are so important.

Oh, and he also threw in this disturbing but excellent point:

You damn well better believe that there is research going on in animal models — what does she expect, that scientists should mutagenize human mothers and chop up baby brains for this work?

If you're interested in watching, Think Progress has a video clip of Palin delivering the remarks. You can read the original prepared text at the McCain campaign page, but they differ somewhat from what she actually said. (For example, sarcasm is not noted anywhere in the prepared text.)

With the election so near (I've been unable to think of anything else lately), I think it's important to recognize what a McCain victory would do to the scientific community. Government funding for basic research is non-negotiable.

Labels:

action alert,

Barack Obama,

citizen science,

community,

education,

election 2008,

politics,

science

Saturday, October 11, 2008

FiveThirtyEight

I can't believe I haven't mentioned this sooner!

If you love number-crunching, politics, statistical research, sociology, or any combination of the above, (or you're a big fan of Obama and want a joyful little reprieve from the woe of the stock market) you will love FiveThirtyEight.com.

There are a lot of polls out there. But any given poll will only survey a few hundred, maybe a few thousand, people at best. With something like 200 million Americans of voting age in this country, how much information can you get from a single poll?

Not much.

That's why a baseball statistician from Chicago named Nate Silver created this marvelous website. He combines polling data from all over the country, assigns a weighting to take into account factors like the number of people interviewed and how reliable a polling company is likely to be, and runs thousands of simulations. All this lets him make predictions about how each state will swing on November 4. (You can read more about the particulars on the FAQ.) These predictions are presented in various ways on the site, but my favorite is the at-a-glance map in the upper right corner.

That map is starting to look a little like my fantasyland map, and I'm tickled dark blue.

The most exciting part recently has been watching states turn white from pale pink, and then slowly, gradually, start turning the palest shade of sky blue... then a little more of a baby blue... and then all of a sudden Virginia is almost as blue as Vermont, Michigan is as blue as Minnesota, and it seems to be spreading from Pennsylvania to Ohio to Indiana.

There's more to the site than the presidential race -- you can read up on the Senate and House races as well. You'll have to sort through that for yourself, as I'm mostly paying attention to the big race (although I like checking the Senate map as well). Enjoy!

If you love number-crunching, politics, statistical research, sociology, or any combination of the above, (or you're a big fan of Obama and want a joyful little reprieve from the woe of the stock market) you will love FiveThirtyEight.com.

There are a lot of polls out there. But any given poll will only survey a few hundred, maybe a few thousand, people at best. With something like 200 million Americans of voting age in this country, how much information can you get from a single poll?

Not much.

That's why a baseball statistician from Chicago named Nate Silver created this marvelous website. He combines polling data from all over the country, assigns a weighting to take into account factors like the number of people interviewed and how reliable a polling company is likely to be, and runs thousands of simulations. All this lets him make predictions about how each state will swing on November 4. (You can read more about the particulars on the FAQ.) These predictions are presented in various ways on the site, but my favorite is the at-a-glance map in the upper right corner.

That map is starting to look a little like my fantasyland map, and I'm tickled dark blue.

The most exciting part recently has been watching states turn white from pale pink, and then slowly, gradually, start turning the palest shade of sky blue... then a little more of a baby blue... and then all of a sudden Virginia is almost as blue as Vermont, Michigan is as blue as Minnesota, and it seems to be spreading from Pennsylvania to Ohio to Indiana.

There's more to the site than the presidential race -- you can read up on the Senate and House races as well. You'll have to sort through that for yourself, as I'm mostly paying attention to the big race (although I like checking the Senate map as well). Enjoy!

Labels:

Barack Obama,

blogs,

citizen science,

community,

election 2008,

politics,

science

Tuesday, October 7, 2008

Uncertainty Parcel Service

I recently ordered something through a website, and the merchant kindly provided a UPS tracking number.

When I clicked through to track my package (still in CA? what's with that?) I ended up on the UPS page. Apparently, UPS now has a new program called "Quantum View". The description is interesting:

Now, of course, the way they want you to parse this paragraph (I believe) is that you can do all of these things with their new program for businesses.

But, given what they've decided to call the program, I'm pretty sure you can only do one or the other. You can find out when your package will arrive, or you can know what city it's in. How uncertain.

When I clicked through to track my package (still in CA? what's with that?) I ended up on the UPS page. Apparently, UPS now has a new program called "Quantum View". The description is interesting:

Quantum View® visibility services help you manage your shipping information securely and efficiently. Whether you want to provide proactive notification to your customers when their shipments are on the way or create a custom tracking report, Quantum View has a solution for you. [emphasis added]

Now, of course, the way they want you to parse this paragraph (I believe) is that you can do all of these things with their new program for businesses.

But, given what they've decided to call the program, I'm pretty sure you can only do one or the other. You can find out when your package will arrive, or you can know what city it's in. How uncertain.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

Better Know an Insect: Just a Little Weevil

I love whole grains, so I keep a variety of them in miscellaneous jars and other storage vessels in a cabinet in my kitchen. I like barley in my soup, curried quinoa, fresh popcorn (no microwave needed!), steel cut oats, and other tasty grains.

Unfortunately, I'm not the only one.

While restocking our popcorn jar, I picked up a bag of barley that I had opened some weeks ago and had rolled and clipped shut. I noticed that some of the barley was... moving. Crawling, really.

This was how we found out that we had an infestation of weevils. More specifically, they were probably wheat weevils, also known as granary weevils, which are a common pest of grain. They look like this:

Unlike the giant water bugs a few months back, however, what you're seeing on your screen is far larger than lifesize. If you check out the post on Wikipedia, you'll see the length given as 3-4 mm from snout-tip to end. These are tiny little critters; they burrow into seeds, very tiny indeed!

Unlike the giant water bugs a few months back, however, what you're seeing on your screen is far larger than lifesize. If you check out the post on Wikipedia, you'll see the length given as 3-4 mm from snout-tip to end. These are tiny little critters; they burrow into seeds, very tiny indeed!

They might be tiny, but they don't lack ambition. We found the majority in the barley, but they'd also made it into the wild rice and the oat bran. (Actually, we caught a mating pair in the act nestled in the oat bran. I'm just glad we found them before it was full of their offspring.) It's not entirely clear -- they may have simply navigated the folds of the bag -- but they may have actually chewed through the plastic to get to the barley. (It was one of those flimsy two-pound bags.)

Anyway, we transferred everything to weevil-proof glass jars and threw the infested materials in the trash.

I don't know how accurate the Wikipedia article is, although the description is true enough. (It's completely lacking in citations.) The page about the weevils as a group is fairly interesting, if brief. It's too bad that the article is so short. There are 60,000 species of weevils in the world, so such a short entry really doesn't do them justice.

Weevils are in Curculionoidea, a superfamily of Coleoptera, or beetles; there are approximately 350,000 described species of beetles total, although there may be as many as 5 million in the world. (This might sound familiar -- frustration with mammal-centrism is part of the reason I do these "Better Know an Insect" posts.) As the visualization goes, if you lined up every known species of animal at random, every fifth one would be a beetle. By comparison, there are fewer than 6000 species of mammal in the world. There are not quite 60,000 species of vertebrates. Yet the gallery for weevils has just a handful of pictures, including the very pretty palmetto weevil.

Even the Encyclopedia of Life has no information about the little granary weevil. The best you can do is the snout beetles page, which has a few nice pictures and a phylogeny but not much besides.

I'm tired and it's nearly Friday, so I'm going to end there for now... but there will be more about other kinds of beetles in the future! There are so many, I could just blog about beetles and have several years' worth of material!

Unfortunately, I'm not the only one.

While restocking our popcorn jar, I picked up a bag of barley that I had opened some weeks ago and had rolled and clipped shut. I noticed that some of the barley was... moving. Crawling, really.

This was how we found out that we had an infestation of weevils. More specifically, they were probably wheat weevils, also known as granary weevils, which are a common pest of grain. They look like this:

Unlike the giant water bugs a few months back, however, what you're seeing on your screen is far larger than lifesize. If you check out the post on Wikipedia, you'll see the length given as 3-4 mm from snout-tip to end. These are tiny little critters; they burrow into seeds, very tiny indeed!

Unlike the giant water bugs a few months back, however, what you're seeing on your screen is far larger than lifesize. If you check out the post on Wikipedia, you'll see the length given as 3-4 mm from snout-tip to end. These are tiny little critters; they burrow into seeds, very tiny indeed!They might be tiny, but they don't lack ambition. We found the majority in the barley, but they'd also made it into the wild rice and the oat bran. (Actually, we caught a mating pair in the act nestled in the oat bran. I'm just glad we found them before it was full of their offspring.) It's not entirely clear -- they may have simply navigated the folds of the bag -- but they may have actually chewed through the plastic to get to the barley. (It was one of those flimsy two-pound bags.)

Anyway, we transferred everything to weevil-proof glass jars and threw the infested materials in the trash.

I don't know how accurate the Wikipedia article is, although the description is true enough. (It's completely lacking in citations.) The page about the weevils as a group is fairly interesting, if brief. It's too bad that the article is so short. There are 60,000 species of weevils in the world, so such a short entry really doesn't do them justice.

Weevils are in Curculionoidea, a superfamily of Coleoptera, or beetles; there are approximately 350,000 described species of beetles total, although there may be as many as 5 million in the world. (This might sound familiar -- frustration with mammal-centrism is part of the reason I do these "Better Know an Insect" posts.) As the visualization goes, if you lined up every known species of animal at random, every fifth one would be a beetle. By comparison, there are fewer than 6000 species of mammal in the world. There are not quite 60,000 species of vertebrates. Yet the gallery for weevils has just a handful of pictures, including the very pretty palmetto weevil.

Even the Encyclopedia of Life has no information about the little granary weevil. The best you can do is the snout beetles page, which has a few nice pictures and a phylogeny but not much besides.

I'm tired and it's nearly Friday, so I'm going to end there for now... but there will be more about other kinds of beetles in the future! There are so many, I could just blog about beetles and have several years' worth of material!

Monday, September 15, 2008

14 Questions

Have you been wondering where Obama and McCain stand on important science issues? Science Debate 2008 can help. They compiled a list of fourteen general questions about important science issues and put them to each of the candidates.

You can read their full responses here. Too busy to scroll all the way down? (Or is the lack of a Web designer hurting your eyes?) Check out the summary published by the NY Times.

Note: You will not find anything about evolution or the teaching thereof in this article. It just didn't figure into the top 14 questions, I guess. I think that's sort of encouraging, but then again, the people asking the questions are scientists. Would I love to hear John McCain say something dumb about evolution? You betcha, but I don't think it's likely; in the Republican primary debates, there was the following exchange:

You can read their full responses here. Too busy to scroll all the way down? (Or is the lack of a Web designer hurting your eyes?) Check out the summary published by the NY Times.

Note: You will not find anything about evolution or the teaching thereof in this article. It just didn't figure into the top 14 questions, I guess. I think that's sort of encouraging, but then again, the people asking the questions are scientists. Would I love to hear John McCain say something dumb about evolution? You betcha, but I don't think it's likely; in the Republican primary debates, there was the following exchange:

MR. VANDEHEI: Senator McCain, this comes from a Politico.com reader and was among the top vote-getters in our early rounds. They want a yes or on. Do you believe in evolution?

SEN. MCCAIN: Yes.

MR. VANDEHEI: I’m curious, is there anybody on the stage that does not agree -- believe in evolution?

(Senator Brownback, Mr. Huckabee, Representative Tancredo raise their hands.)

SEN. MCCAIN: May I -- may I just add to that?

MR. VANDEHEI: Sure.

SEN. MCCAIN: I believe in evolution. But I also believe, when I hike the Grand Canyon and see it at sunset, that the hand of God is there also.

So, there's that. But, I also think McCain is slippery enough to try to get out of that one too, especially with what's-her-name in the game now. Gotta love how he has to qualify his acceptance (we don't like to say belief) of evolution. Also love that they work in some discussion of sustainable seafood! Anyway, now I'm going off on a tangent. Enjoy the articles!

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Too Cool

So, it turns out that I'm rather allergic to certain moisturizers, or some ingredient therein.

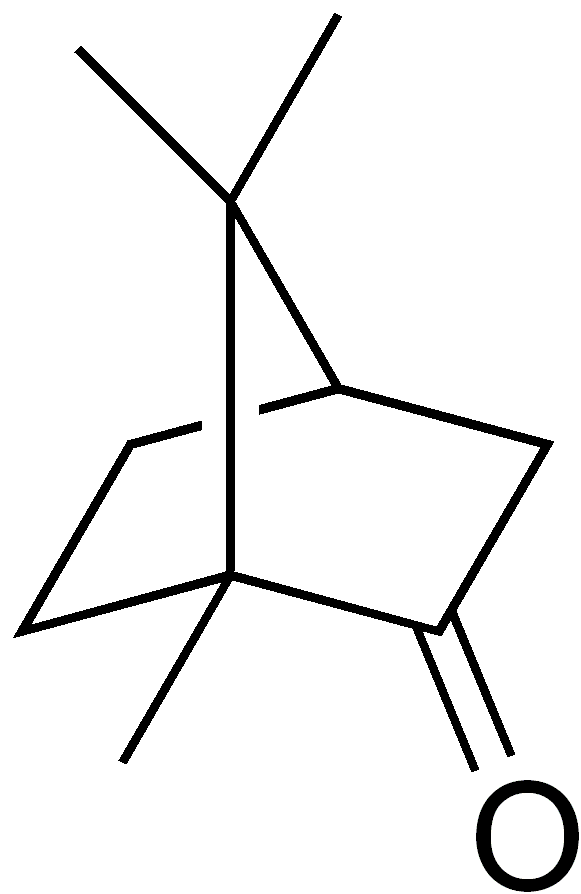

In addition to some serious topical steroid cream which required a prescription, my dermatologist suggested a lotion called Sarna* as an additional treatment/source of salvation. (A salve of salvation?) What's the magic ingredient? There are two, actually: camphor and menthol.

Naturally-derived camphor is a tree resin that is solid at room temperature. It is also highly flammable, which I learned from The Time Machine. Not surprisingly, it has some insect-repellent qualities (of course it does, plants need defenses too!). Some mothballs are made with camphor. It is also a rather effective topical analgesic.

It is interesting to note that natural camphor is derived from the camphor laurel, Cinnamomum camphora. That genus name isn't a coincidence; true cinnamon (C. verum) and cassia (C. aromaticum, which is most common "cinammon" sold in America) are in the same genus as camphor. Camphor laurels are an economically important crop in the areas where the species is native, but the tree is invasive in Australia. Camphor was also one of the first organic chemicals to be synthesized in a laboratory.

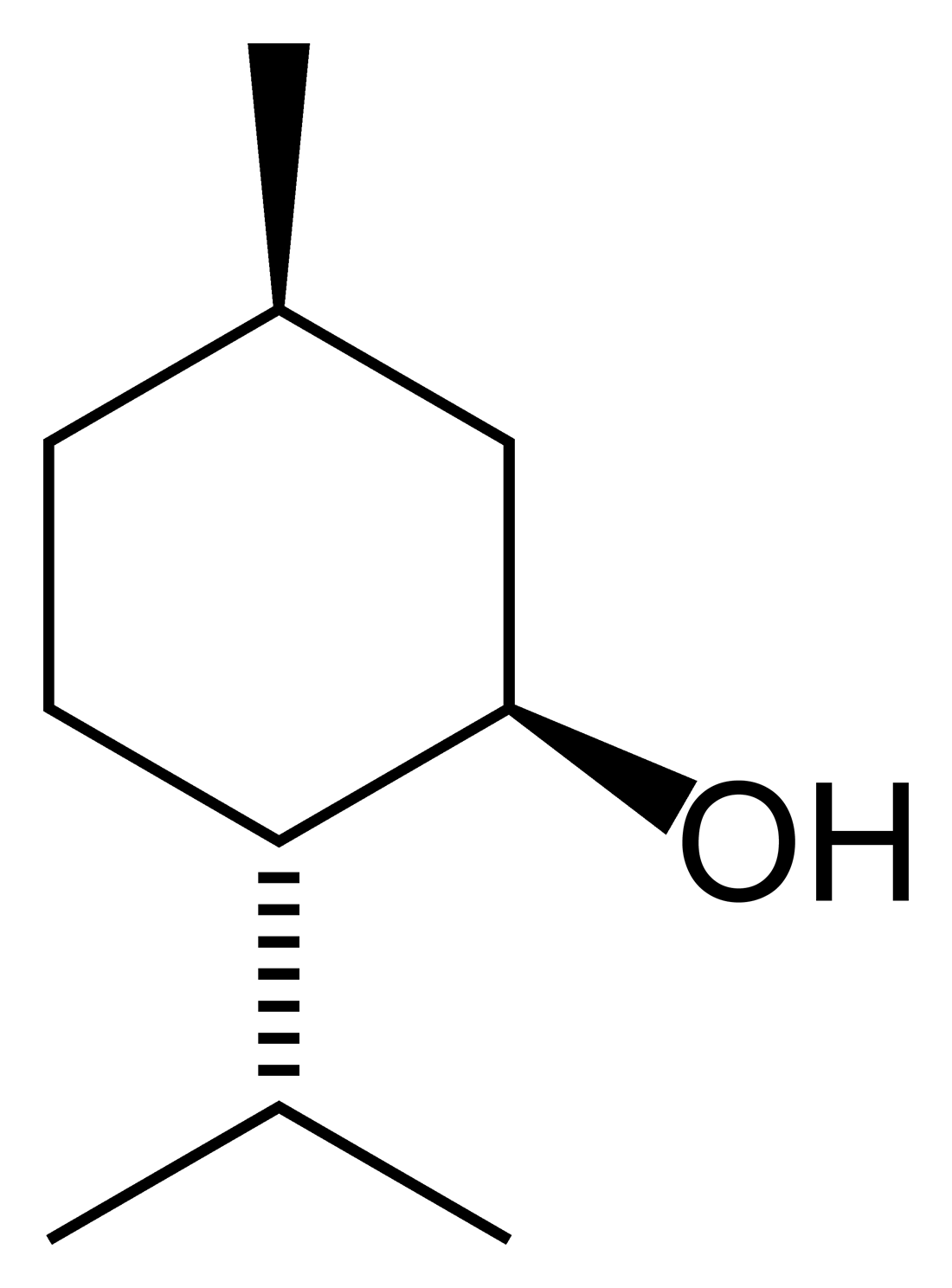

Menthol is the other half of this dynamic duo. Menthol can also be synthesized in the lab, but in nature it is found in members of Mentha, the genus that includes peppermint (Mentha x piperita, actually a well-established hybrid of watermint and spearmint), spearmint (Mentha spicata), and other pleasant-smelling herbs.

I don't know which of these compounds acts faster and which one lasts longer, but combined they're enough to stop itching cold. (Sorry.) Menthol stimulates specific cold-sensitive ion channels in skin neurons, but I'm not sure how camphor works. In my case, the combination of menthol and camphor creates such a strong illusion of cold that I start shivering even though I know my body is at an acceptable room temperature.

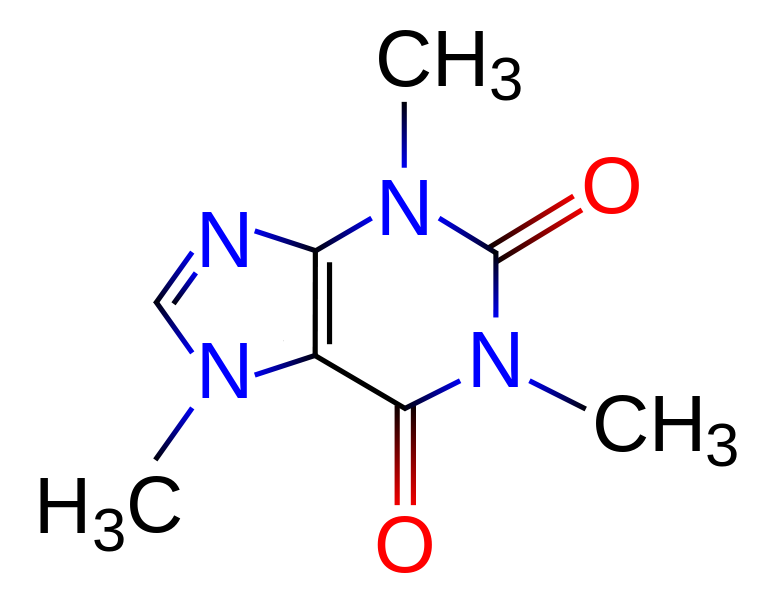

I would write more -- allergies are incredibly interesting and very complicated -- but I'm also taking diphenhydramine and I feel like I'm about to zonk out. (And it's only 11 AM!) I'd better prepare some coffee.

Oh, organic chemistry, is there anything you can't do?

*As an interesting aside, sarna apparently means "scabies" in Spanish.

In addition to some serious topical steroid cream which required a prescription, my dermatologist suggested a lotion called Sarna* as an additional treatment/source of salvation. (A salve of salvation?) What's the magic ingredient? There are two, actually: camphor and menthol.

Naturally-derived camphor is a tree resin that is solid at room temperature. It is also highly flammable, which I learned from The Time Machine. Not surprisingly, it has some insect-repellent qualities (of course it does, plants need defenses too!). Some mothballs are made with camphor. It is also a rather effective topical analgesic.

It is interesting to note that natural camphor is derived from the camphor laurel, Cinnamomum camphora. That genus name isn't a coincidence; true cinnamon (C. verum) and cassia (C. aromaticum, which is most common "cinammon" sold in America) are in the same genus as camphor. Camphor laurels are an economically important crop in the areas where the species is native, but the tree is invasive in Australia. Camphor was also one of the first organic chemicals to be synthesized in a laboratory.

Menthol is the other half of this dynamic duo. Menthol can also be synthesized in the lab, but in nature it is found in members of Mentha, the genus that includes peppermint (Mentha x piperita, actually a well-established hybrid of watermint and spearmint), spearmint (Mentha spicata), and other pleasant-smelling herbs.

I don't know which of these compounds acts faster and which one lasts longer, but combined they're enough to stop itching cold. (Sorry.) Menthol stimulates specific cold-sensitive ion channels in skin neurons, but I'm not sure how camphor works. In my case, the combination of menthol and camphor creates such a strong illusion of cold that I start shivering even though I know my body is at an acceptable room temperature.

I would write more -- allergies are incredibly interesting and very complicated -- but I'm also taking diphenhydramine and I feel like I'm about to zonk out. (And it's only 11 AM!) I'd better prepare some coffee.

Oh, organic chemistry, is there anything you can't do?

*As an interesting aside, sarna apparently means "scabies" in Spanish.

Thursday, August 21, 2008

Correction

Just a quick FYI -- thanks to Mike, I can now inform you that the dragonfly I previously labeled L. vibrans (great blue skimmer) is actually L. incesta (slaty skimmer). Apparently, vibrans has a whitish face, which indicates that this is incesta. I do not know how it came to that species name, however. That's all for now!

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

Better Know an Insect: Anax junius, part I

I post a lot about what's going on in the world of science, but I haven't posted much about what I'm doing.

Today, that changes.

Ladies and gents, this is Anax junius, the green darner dragonfly:

Take a good look, because you'll be hearing a lot about these guys in the future.

Today was a testing day for Mike and myself. (Mike is my advisor.) We received some very small transmitters a few weeks ago, but because of various things (his trip to South Africa, my shuffling between NJ and LI, logistics, etc.) the plan finally came together only this week.

(Please bear with me. I forgot my camera, I will try to describe things as well as I can, and I will hopefully have some more pictures tomorrow.)

After borrowing a van from Princeton, which may or may not prove handy depending on how well we can use our radio antenna, we headed to a pond and spotted a few Anax. Mike being in possession of the one pair of waders, he went on in while I stayed on shore in case any made an escape attempt in my direction. We were very lucky, and Mike bagged a male (like the picture above) within a few minutes. Back on shore, we sat down in the shade (don't want the little guy to overheat) and proceeded to apply a radio transmitter with a combination of eyelash adhesive and crazy glue. Once it was on, he sat on Mike's finger, shivered his flight muscles for a few minutes to warm back up, and took off.

We were able to follow him for a bit into some trees (apparently, green darners that have been man-handled will retreat to trees away from the pond) and then lost the signal. Driving around, we were able to find his blip again, only to lose it a few minutes later. We are concerned that the soldering was not as firm as we'd like and the transmitter may only be transmitting intermittently (that's a mouthful!).

Our plan for tomorrow is to 1) try to find our guy again in the same area. If we are successful... well, actually I don't know. I think we'll just try to keep an eye on him as long as we can. 2) If we can't find him, we'll first do a practice run with just a transmitter to test the range of a properly-functioning beacon. After that... probably try to bag another one and follow it around for a while.

What's the point of all this? Well, our project is on migration in Anax. So, we're trying to figure out whether it's even feasible to tag one, relocate it, and follow it for several days over land. It has been done before, but we're both new-ish to the technique. And it's not easy.

I'll post more in the next few days about the exciting world of insect endocrinology and how hormones may influence migratory behavior -- an under-explored area which might become part or all of my project if it proves too difficult to consistently follow tagged individuals. Also, pictures next time.

PS: In case you were thinking that we were attaching big, heavy transmitters to dainty damselflies, rest assured, we are not. Green darners are anything but dainty. Go out to a pond, take a look at all the dragonflies you see, and look for the biggest thing flying around. That's probably an Anax species. A picture for size comparison:

I didn't take this picture and those aren't my hands, but this will give you some idea of just how big these guys are. Totally harmless, of course, but definitely massive!

Today, that changes.

Ladies and gents, this is Anax junius, the green darner dragonfly:

Take a good look, because you'll be hearing a lot about these guys in the future.

Today was a testing day for Mike and myself. (Mike is my advisor.) We received some very small transmitters a few weeks ago, but because of various things (his trip to South Africa, my shuffling between NJ and LI, logistics, etc.) the plan finally came together only this week.

(Please bear with me. I forgot my camera, I will try to describe things as well as I can, and I will hopefully have some more pictures tomorrow.)

After borrowing a van from Princeton, which may or may not prove handy depending on how well we can use our radio antenna, we headed to a pond and spotted a few Anax. Mike being in possession of the one pair of waders, he went on in while I stayed on shore in case any made an escape attempt in my direction. We were very lucky, and Mike bagged a male (like the picture above) within a few minutes. Back on shore, we sat down in the shade (don't want the little guy to overheat) and proceeded to apply a radio transmitter with a combination of eyelash adhesive and crazy glue. Once it was on, he sat on Mike's finger, shivered his flight muscles for a few minutes to warm back up, and took off.

We were able to follow him for a bit into some trees (apparently, green darners that have been man-handled will retreat to trees away from the pond) and then lost the signal. Driving around, we were able to find his blip again, only to lose it a few minutes later. We are concerned that the soldering was not as firm as we'd like and the transmitter may only be transmitting intermittently (that's a mouthful!).

Our plan for tomorrow is to 1) try to find our guy again in the same area. If we are successful... well, actually I don't know. I think we'll just try to keep an eye on him as long as we can. 2) If we can't find him, we'll first do a practice run with just a transmitter to test the range of a properly-functioning beacon. After that... probably try to bag another one and follow it around for a while.

What's the point of all this? Well, our project is on migration in Anax. So, we're trying to figure out whether it's even feasible to tag one, relocate it, and follow it for several days over land. It has been done before, but we're both new-ish to the technique. And it's not easy.

I'll post more in the next few days about the exciting world of insect endocrinology and how hormones may influence migratory behavior -- an under-explored area which might become part or all of my project if it proves too difficult to consistently follow tagged individuals. Also, pictures next time.

PS: In case you were thinking that we were attaching big, heavy transmitters to dainty damselflies, rest assured, we are not. Green darners are anything but dainty. Go out to a pond, take a look at all the dragonflies you see, and look for the biggest thing flying around. That's probably an Anax species. A picture for size comparison:

I didn't take this picture and those aren't my hands, but this will give you some idea of just how big these guys are. Totally harmless, of course, but definitely massive!

Labels:

animal behavior,

animals,

better know an insect,

ecology,

habitat,

science

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Chocolate-Covered Enzymes

Flipping through bridal magazines, you see many cakes. A majority of them, at least the über-fancy ones, are covered in fondant. Fondant (for those of you not shopping for pastry at the moment) is what makes cakes look like this:

A cake frosted with buttercream, on the other hand, looks more like this:

Both cakes look lovely, but notice how the top cake is so smooth and sculptural, while the bottom one (which in my opinion looks more delicious anyway) is a little rougher; there are little air bubbles and minor imperfections along the sides, the lines aren't quite perfect.

"What the heck does this have to do with science? I didn't come to this site to read about fondant vs. buttercream! I demand an explanation!"

Let's start out just talking about fondant. Fondant is a heavy paste which, at its most basic, is made with just water, sugar, a little food coloring, and a skilled hand. (A candy thermometer helps, and there are many variations using different sugar ingredients.) If you accidentally jolt the bowl while it's cooling, the sugar will come out of solution quickly and in large crystals; presto, rock candy!

However, by mixing the water and sugar together at a high temperature and then cooling it very gently, stirring violently at the very end, the supersaturated solution forms very tiny crystals that look as smooth as a lake on a calm day. You can use this paste to decorate cakes in myriad ways -- a quick Google images search for fondant cakes will give you an idea of just how many! You can sculpt with it. You can cut it and shape it. And, for all intents and purposes, you can even eat it. (Although not that many people do.)

Now, if you made fondant from scratch, you would likely just use sucrose -- that is, ordinary table sugar.

And if you cut that piece of fondant into squares and dipped them into chocolate, you would have this:

"But wait! The inside of an After Eight mint is so creamy and soft! There's no way it could be the same as that stiff piece of fondant covering the cake up there!"

Ah. Yes. You have a point.

And that is where the enzymes come in. Invertase is a naturally-occurring enzyme produced by some bacteria as well as some animals that breaks down sucrose into its component sugars, glucose and fructose, which is sometimes known as inverted sugar syrup. (The reason for "invert" is interesting but I can't explain it well; read about it here.)

In the production of After Eight mints, a small amount of invertase is added to the minty fondant just before it is coated with chocolate. The enzyme doesn't begin to work immediately, so the chocolate can cool around the fondant before it begins to "cure". The smaller, more soluble molecules of glucose and fructose go into solution more readily and disolve in the small amount of water contained in the fondant; it isn't enough to create a runny liquid, but it's enough that when you bite into an After Eight (or any other fondant-filled treat) the texture is creamy and viscous and not a stiff paste.

Mmm, enzymes. What can't they do?

PS: On a totally unrelated note, we just watched the first segment of Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog. Hilarious! So much fun! Go watch while you can, it's gone on Sunday.

A cake frosted with buttercream, on the other hand, looks more like this:

Both cakes look lovely, but notice how the top cake is so smooth and sculptural, while the bottom one (which in my opinion looks more delicious anyway) is a little rougher; there are little air bubbles and minor imperfections along the sides, the lines aren't quite perfect.

"What the heck does this have to do with science? I didn't come to this site to read about fondant vs. buttercream! I demand an explanation!"

Let's start out just talking about fondant. Fondant is a heavy paste which, at its most basic, is made with just water, sugar, a little food coloring, and a skilled hand. (A candy thermometer helps, and there are many variations using different sugar ingredients.) If you accidentally jolt the bowl while it's cooling, the sugar will come out of solution quickly and in large crystals; presto, rock candy!

However, by mixing the water and sugar together at a high temperature and then cooling it very gently, stirring violently at the very end, the supersaturated solution forms very tiny crystals that look as smooth as a lake on a calm day. You can use this paste to decorate cakes in myriad ways -- a quick Google images search for fondant cakes will give you an idea of just how many! You can sculpt with it. You can cut it and shape it. And, for all intents and purposes, you can even eat it. (Although not that many people do.)

Now, if you made fondant from scratch, you would likely just use sucrose -- that is, ordinary table sugar.

And if you cut that piece of fondant into squares and dipped them into chocolate, you would have this:

"But wait! The inside of an After Eight mint is so creamy and soft! There's no way it could be the same as that stiff piece of fondant covering the cake up there!"

Ah. Yes. You have a point.

And that is where the enzymes come in. Invertase is a naturally-occurring enzyme produced by some bacteria as well as some animals that breaks down sucrose into its component sugars, glucose and fructose, which is sometimes known as inverted sugar syrup. (The reason for "invert" is interesting but I can't explain it well; read about it here.)

In the production of After Eight mints, a small amount of invertase is added to the minty fondant just before it is coated with chocolate. The enzyme doesn't begin to work immediately, so the chocolate can cool around the fondant before it begins to "cure". The smaller, more soluble molecules of glucose and fructose go into solution more readily and disolve in the small amount of water contained in the fondant; it isn't enough to create a runny liquid, but it's enough that when you bite into an After Eight (or any other fondant-filled treat) the texture is creamy and viscous and not a stiff paste.

Mmm, enzymes. What can't they do?

PS: On a totally unrelated note, we just watched the first segment of Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog. Hilarious! So much fun! Go watch while you can, it's gone on Sunday.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Better Know an Insect: Femme Fatale Fireflies

Last night Dustin and I took an evening stroll through the park. It was a lovely, warm evening, with robins singing from the treetops and a slight breeze rustling the grass. And, of course, there were fireflies, lighting up the summer night with their romantic display, a visual analog to a bird's song.

Males, seeking females, blink their message in code, while females sit and wait on the ground for the right guy to come along. When she sees him, she blinks back until he finds her, and that's where baby fireflies come from. Aww.

Unless she's a hungry female of the genus Photuris, that is.

After Photuris females have mated, they don't need to mate again. But why waste a perfectly good signaling device? Instead, the Photuris females signal back to males of another species, Photinus, luring them in and catching them for dinner. Delicious!

But he's not just a tasty meal to help her lay eggs. It turns out that Photinus males produce a chemical that protects them from attacks by spiders and other arthropod predators. By eating Photinus males, the Photuris female acquires this armor and is herself protected from attack.

So, the next time you're out for an evening stroll in July, consider the drama playing out before you. There are dangerous femme fatales everywhere you look.

Read more about it on this page from Cornell.

Males, seeking females, blink their message in code, while females sit and wait on the ground for the right guy to come along. When she sees him, she blinks back until he finds her, and that's where baby fireflies come from. Aww.

Unless she's a hungry female of the genus Photuris, that is.

After Photuris females have mated, they don't need to mate again. But why waste a perfectly good signaling device? Instead, the Photuris females signal back to males of another species, Photinus, luring them in and catching them for dinner. Delicious!

But he's not just a tasty meal to help her lay eggs. It turns out that Photinus males produce a chemical that protects them from attacks by spiders and other arthropod predators. By eating Photinus males, the Photuris female acquires this armor and is herself protected from attack.

So, the next time you're out for an evening stroll in July, consider the drama playing out before you. There are dangerous femme fatales everywhere you look.

Read more about it on this page from Cornell.

Labels:

animal behavior,

animals,

better know an insect,

education,

evolution,

science

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Better Know an Arthropod: Bizzaro Lobsters!

Most people are familiar with the lobsters that grace many New England tables this time of year. The American/Atlantic/Maine lobster, Homarus americanus, is a well-known icon of the northeast part of the country and countless J. Crew summer prints.

Therefore, we're not going to discuss them further here today. Perhaps once I read The Secret Life of Lobsters I'll have something interesting to say about them beyond that they're apparently good with drawn butter.

This post is about the bizarro-lobsters of the deep seas. Sharon introduced me to a new one today, so let's view that one first!

The slipper lobster is not a "true lobster" -- it is instead more closely related to some of the other bizarro lobsters, the spiny and furry lobsters. They are achelate, meaning they have no claws. This makes them easy prey for humans, and indeed, if you Google "slipper lobster" you will find their tail meat for sale. (Of course, there is no claw meat to speak of.) Some of them are actually referred to as bugs, which is rather entertaining. No word yet on their position as a sustainable seafood. Not much seems to be known about them, if Wikipedia is at all accurate. Maybe it's better that way.

Next up: spiny lobsters. Popular for eating, also known as "rock lobster", and very colorful. Also, the only arthropod (as far as I know) that was immortalized in song by Fred Schneider (who is also very colorful). Interestingly, spiny lobsters have a unique form of sound production involving rubbing their antennae against a file-like protrusion. I'm not really sure what's going on there, but they're the only ones that do it, so that's neat.

I would tell you something about the furry lobsters, but there doesn't seem to be much to tell. (Except that if you start thinking too hard about the concept of a furry lobster, it can sort of hurt your brain.) Besides, you don't want to hear about true furry lobsters, you want to hear about this:

Kiwa hirsuta, also entertainingly known as the yeti lobster, is not a true lobster or in the Achelate group with the other "bizarro" lobsters. Kiwa is in its own brand-new family, Kiwaidae, all by its lonesome. See, this beautiful, samba-dancing lobster, which you might be tempted to call a furry lobster but is not, was only discovered in 2005, chillin' at the bottom of the Pacific ocean. It lives on hydrothermal vents (so, maybe not chillin', per se), is pretty much blind, and may use all those "hairs" to detox after hanging around the vents, which spew mineral toxins.

My favorite part of this lobster is not that it's yellow, not that it's furry, and not that it's a deep-sea critter. (Although I love deep-sea critters, they're so bizarre!) My favorite part is that it was only found three years ago. I spent most of my life on a planet where no humans knew this thing existed! I suppose Kiwa knew it existed, if decapods can have self-awareness. But we did not know. There are still new things out there to find, if we look hard enough! (As I mentioned in my previous post, the world is just awesome.)